Term time has returned to England’s cathedral cities and University Challenge is back on our screens. Just as night follows day, thus has begun the debate over why the Monday night staple is still so male decades after women first outnumbered men at university. The canonical answers are women feeling less comfortable showing off their intelligence, bias in the selection process and the alleged disproportionate amount of abuse female contestants receive on Twitter.

But given my knowledge of how individuals qualify for the show, I suspect the true explanation is less flattering to women. Participants have been selected by trials that mimic the programme. Each institution receives an application pack from the BBC, which contains questions typical of those that would appear on University Challenge. The quiz society (or the JCR for Oxbridge colleges) runs an open competition where each trialist is ranked by the number of questions they answer correctly.

One might think the top five (four and one reserve) are chosen to represent the institution in the audition with the show’s producers, which involves another gruelling round of questions. But according to a friend of mine who appeared on the programme, the producers also specify that they’re more likely to select a team which is “diverse” along the axes of “gender, race, accent and field of study”. Many teams reserve a spot for a woman to increase their chances of appearing on television, which makes the allegations of bias against women hard to believe.

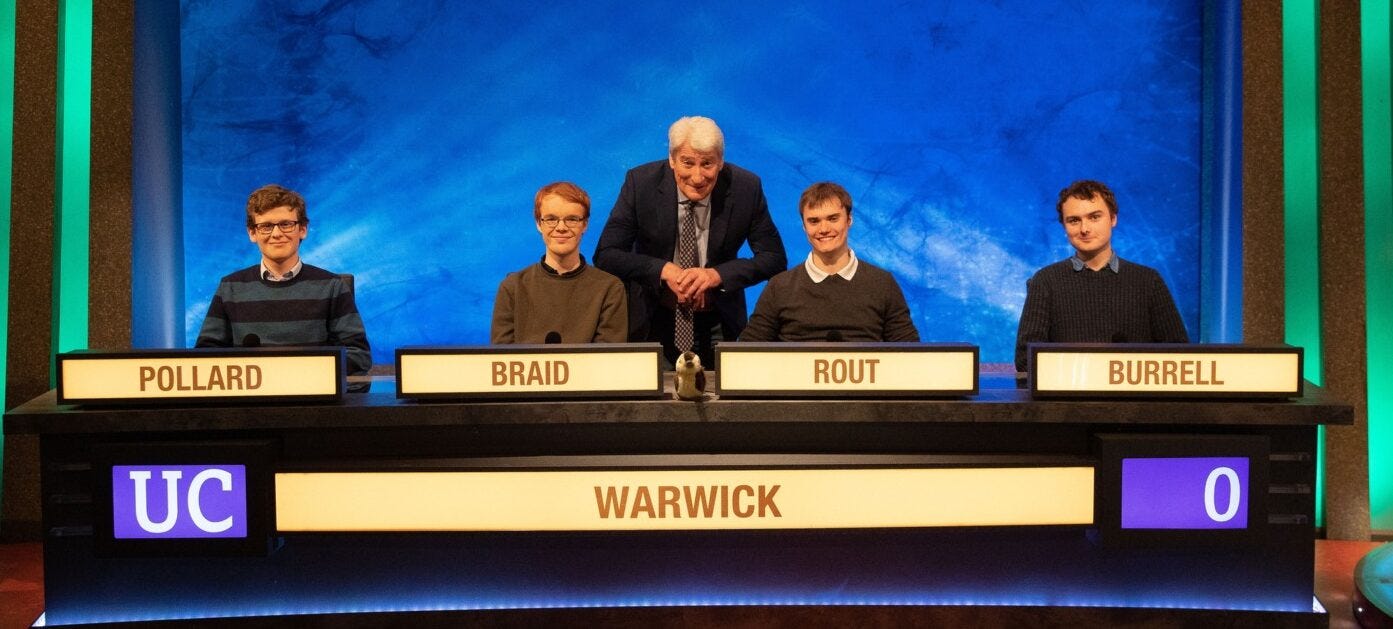

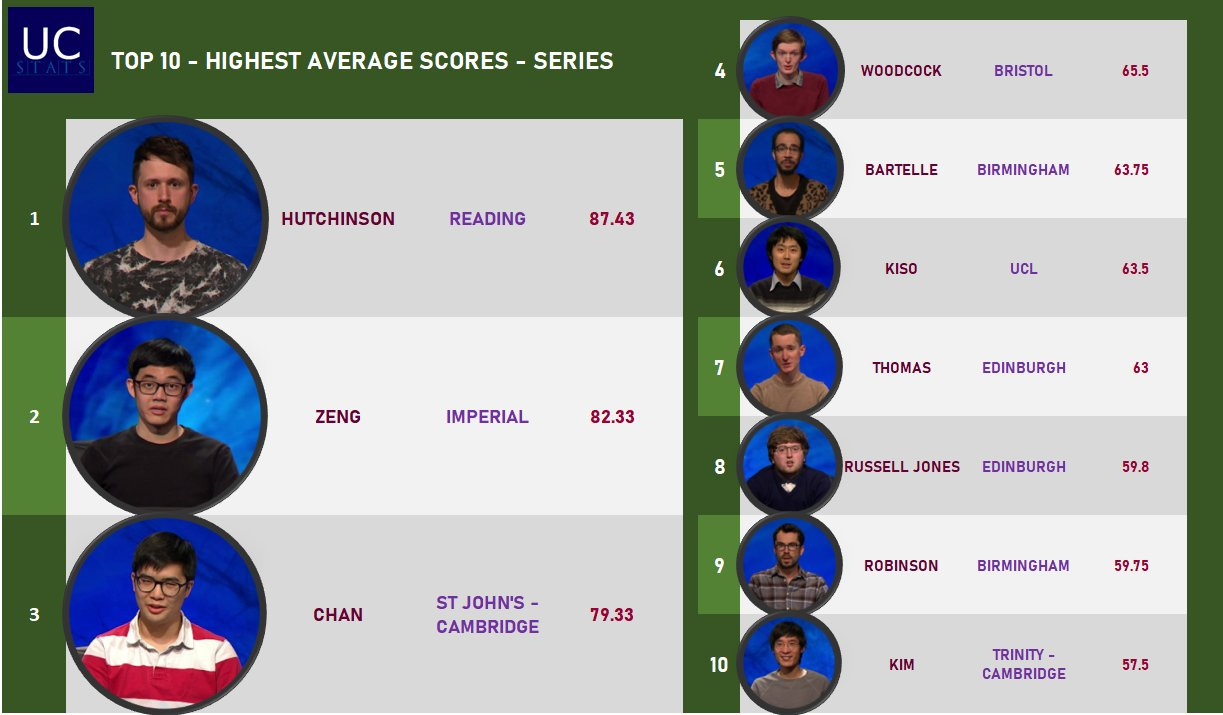

When this process is finished thousands of hopefuls have been whittled down to just 112 competitors. Over three quarters are male, despite the attempts to engineer a gender balance. This selection is reflective of the programme itself, which suggests the most plausible explanation for male overrepresentation is that men have a large advantage in general knowledge. This argument could be sustained by simply watching the show. Men are more likely to be captains and the highest scoring players are one hundred percent male.

This conclusion is supported by psychometric evidence. Pew found that American men who had some college experience (but never graduated) had the same general scientific knowledge as women who had completed a postgraduate degree. Similar surveys found men had greater knowledge of religion, international affairs, technology and even the Holocaust. This isn’t surprising for anyone who has ever talked to a woman. When canvassing my friends for the article I was overwhelmed with anecdotes of intelligent women who lacked basic general knowledge.

A woman I studied with who had a £45k graduate job in the City aged 22 asked a Jordanian we knew if Jordan was “in the northern or southern hemisphere”

Senior women professionals I worked with on my own graduate scheme couldn’t recognise flags of countries like Brazil or South Africa during a Zoom quiz

A woman who lives on a friend’s street couldn’t name a single English county when asked (granted he tells me she is only of average intelligence)

A friend knows a woman who thought Kent was a city despite having been to Kent, and another friend knew a woman who thought that Leeds was in Kent (because of Leeds Castle)

A woman studying for a masters degree in philosophy alongside a friend did not know when the First World War took place

A woman the same friend knows thought the Spartans were a fictional people after seeing the film 300

A woman who worked with a friend did not know the Queen’s name was Elizabeth

A woman a friend studied with made it to graduate school believing Austria was a fictional country

And a girl in a friend’s GCSE religion lessons who eventually went to Oxford did not know that Catholics were Christians

There are also examples of this phenomenon in public life. When asked by Sergei Lavrov whether Britain recognised Russian sovereignty over Rostov, then Foreign Secretary Liz Truss let slip that she believed that Rostov was in Ukraine. Worse still was Karen Bradley's revelation upon being appointed Northern Ireland Secretary she didn’t know elections in the province were fought along sectarian lines. Yet, all (bar one) of the women in these stories are from the Russell Group, the ‘laptop class’ or ‘the cognoscenti’, so it’s hardly surprising that women struggle at quiz shows.

The idea this is due to women’s greater modesty is incongruent with the similar results we see in competitions where money is on the line. Sixteen of eighteen winners of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? have been men. And who isn’t familiar with the season of ‘disso’ pictures of beaming young women displaying The Feminist Interpretation of Wuthering Heights or The Effect of Boris Johnson’s Editorship of the Spectator on the Mental Health of Black Britons?

All of this confirms that women struggle with general knowledge. But how can we quantify the disparity?

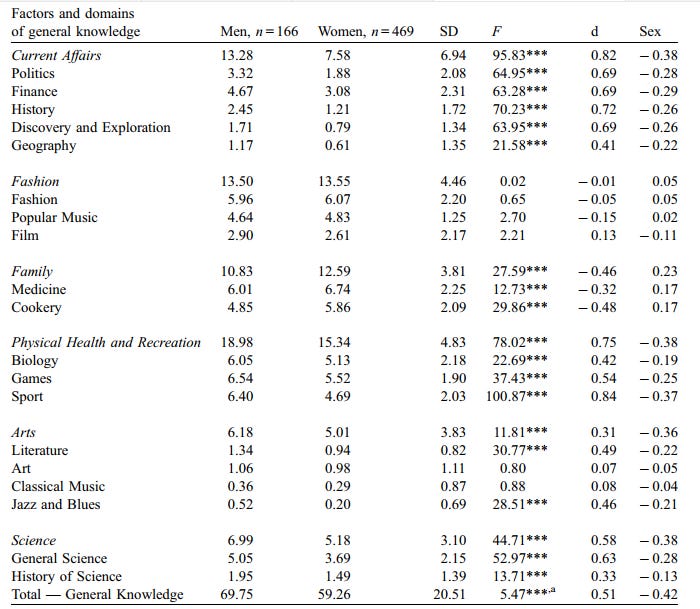

One study showed that men have a half a standard deviation advantage in general knowledge - equivalent to 7.5 IQ points. The most knowledgeable 1% of the population, those likely to appear on University Challenge, would be 79% male. This is as large as the well-known male superiority in visuo-spatial reasoning1. One could argue that this is an artefact of construction: in a patriarchal society, facts more available to men are considered to merit status as 'general knowledge', so of course men will display an edge - or so the argument goes. But in fashion and popular music there is no statistically significant difference between the sexes. Women only show greater general knowledge in medicine and cooking, and the disparity in these subjects is much smaller than in areas where men hold the upper-hand, such as science, history, geography and politics.

So men’s predominance on University Challenge is due to the simple fact they know more about the world. But is general knowledge actually useful?

Men are also more numerous among the top ranks of historians, journalists and even Substackers, so perhaps having an eclectic hoard of knowledge is useful as an intellectual. It’s also a deeper skill than an ability to unthinkingly recall trivia: general knowledge is strongly predictive of general intelligence (‘g’), the engine room behind IQ. It consistently ranks as one of the most ‘g-loaded’ subtests, alongside vocabulary and arithmetic. The best players on University Challenge deploy their ability to quickly draw inferences when jumping the gun on Jeremy Paxman or their mathematical dexterity when calculating modular arithmetic at lightning speed.

That Oxbridge colleges routinely triumph over universities with a talent pool an order of magnitude greater suggests human capital is highly concentrated at England’s two ancient universities. Suspicion that their graduates take too many of the country’s top jobs is misplaced. Like the ‘Just Blokes’ makeup of University Challenge, it’s a consequence of differences in cognitive ability between different parts of the population. Though the former is a more dangerous manifestation of the blank slate ideology, the attempt to shrink the presence of men on the TV quiz show should be resisted.

Chapter 10, Sex Differences in Intelligence: The Developmental Theory, Richard Lynn (2021)